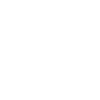

Banned & Censored, selected and introduced by Devika Sethi, will take you on a journey of words and ideas that were deemed dangerous and seditious by the British colonial state in the eventful first half of the twentieth century in India. If censorship gives us an insight into the weaknesses of a state – its many Achilles’ heels, as it were – these texts collectively map the anxieties of the colonial state. They also reveal to us individuals, events and ideas that have shaped India’s present. Changes in the tone and tenor of these banned texts reveal the limits of tolerance as the century progressed.

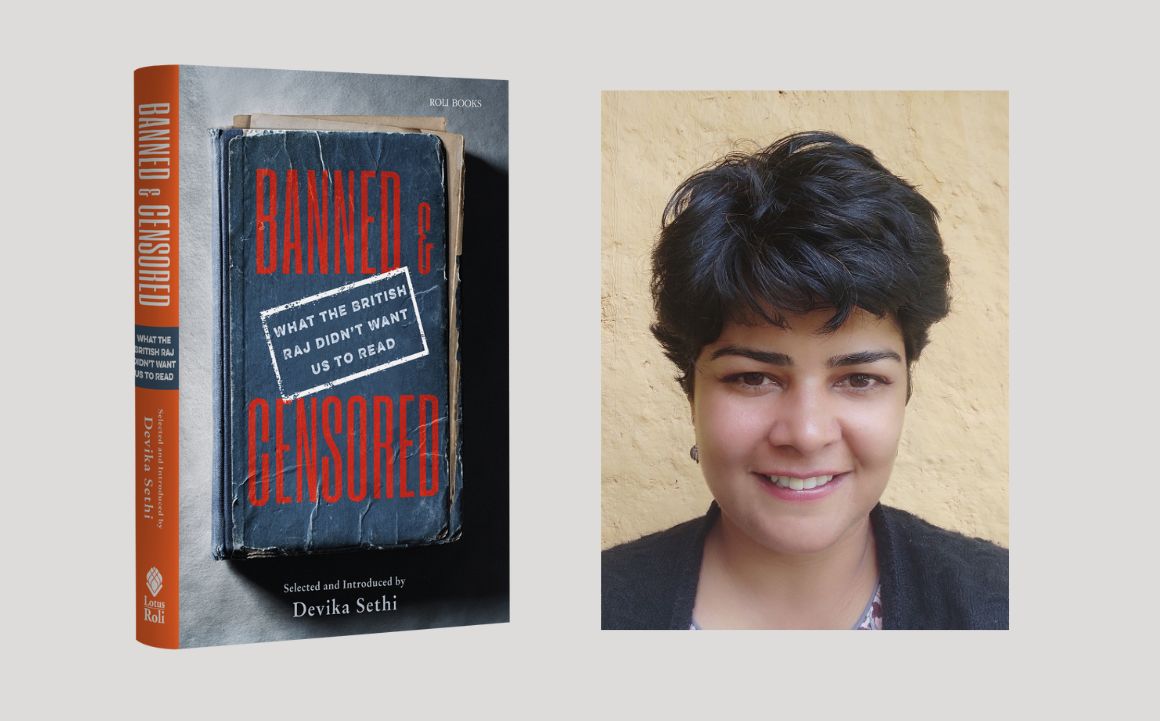

Kesari was a Marathi weekly started by Bal Gangadhar Tilak (1856–1920) in 1880. In June 1897, he had been sentenced to 18 months’ imprisonment for verses published in the journal. Six months of the sentence were remitted once Tilak agreed to certain conditions.

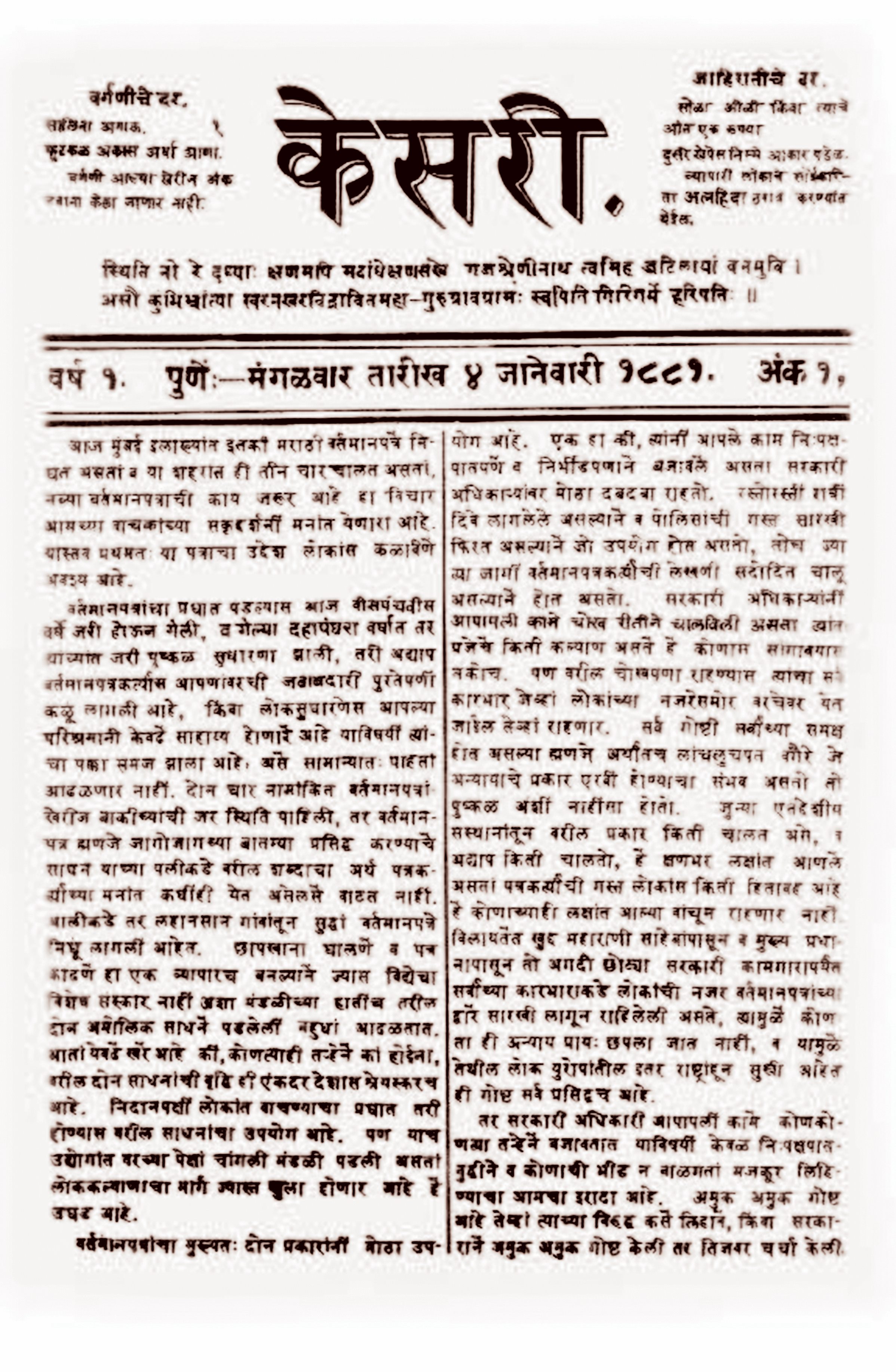

The Indian Sociologist was a monthly that was issued between 1905 and 1914 by Shyamji Krishnavarma (1857–1930), mentor and patron of the first generation of Indian revolutionaries. After Sir Curzon Wyllie’s assassination in London, the monthly came under the scanner for words of approbation. Even as Krishnavarma escaped from prosecution on account of his migration to Paris, two consecutive English printers of the journal were sentenced to jail.

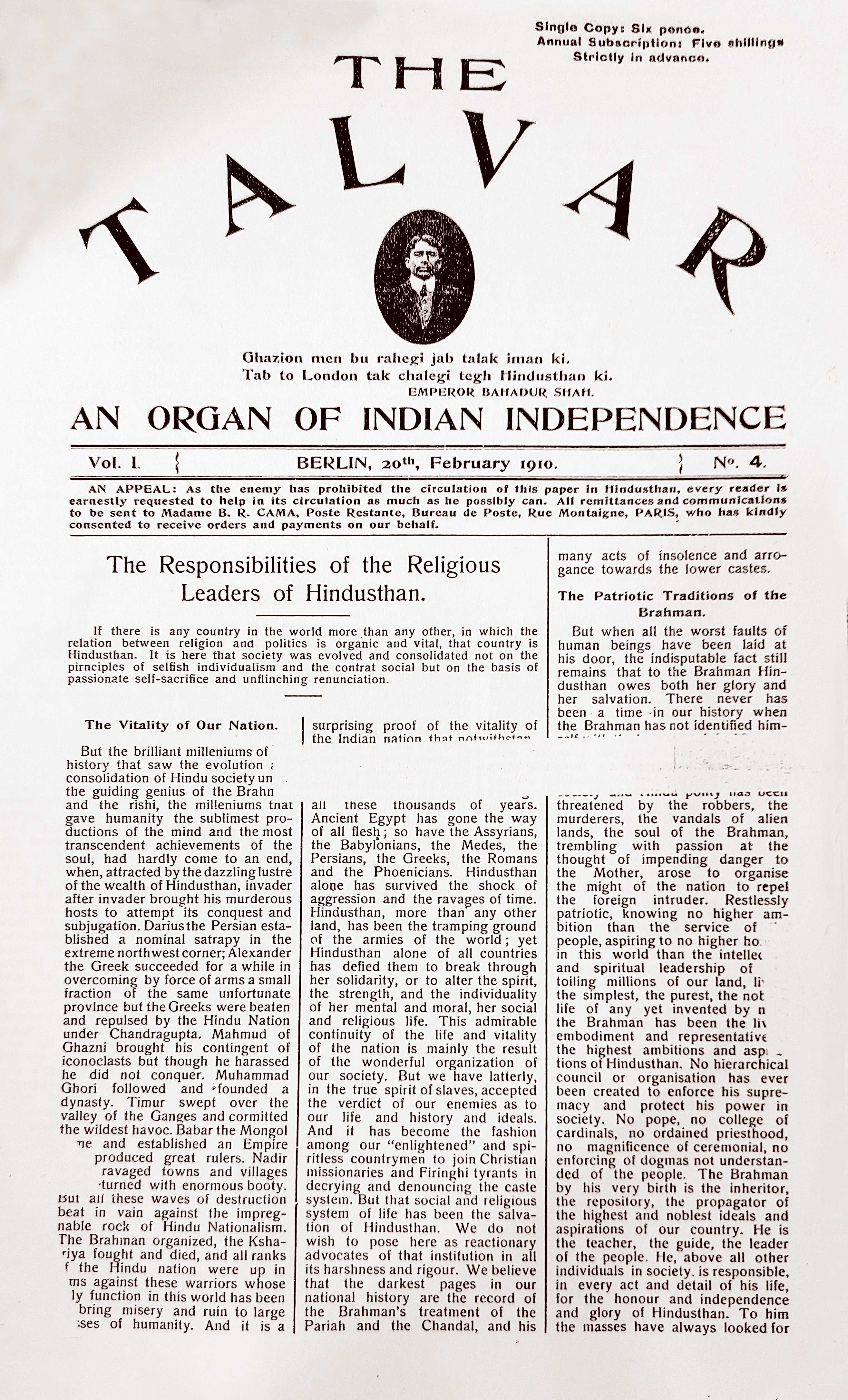

Banned both by local governments, as well as under the Sea Customs Act, in its February issue, the following appeal was printed just below the header, with Madame Cama mentioned as the person to whom orders and payments had to be made:

AN APPEAL: As the enemy has prohibited the circulation of this paper in Hindusthan, every reader is earnestly requested to help in its circulation as much as he possibly can.

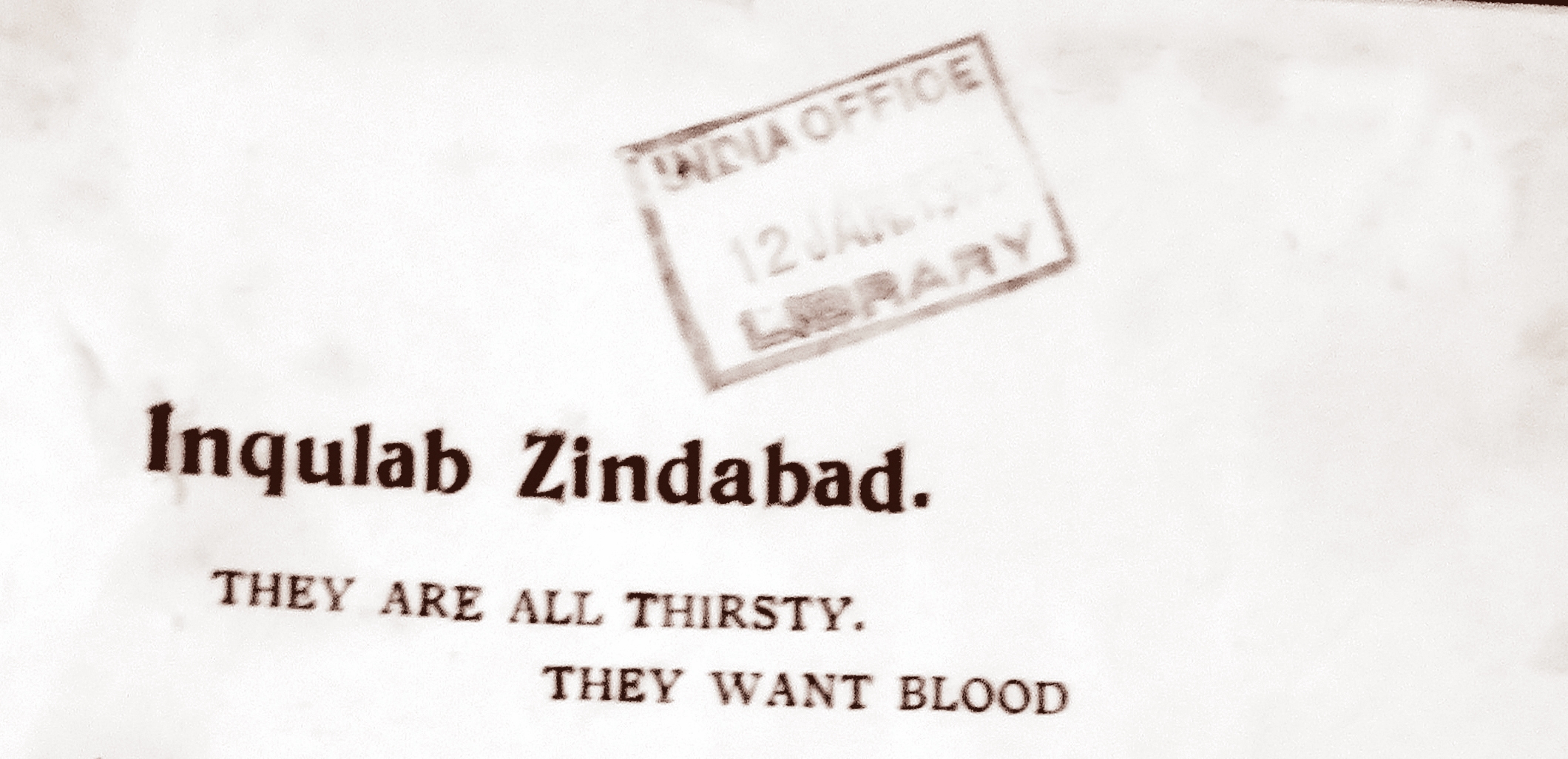

This pamphlet, with an Urdu title that had by now become a popular revolutionary slogan, vividly captured the mood of extreme anger after the execution of Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev.

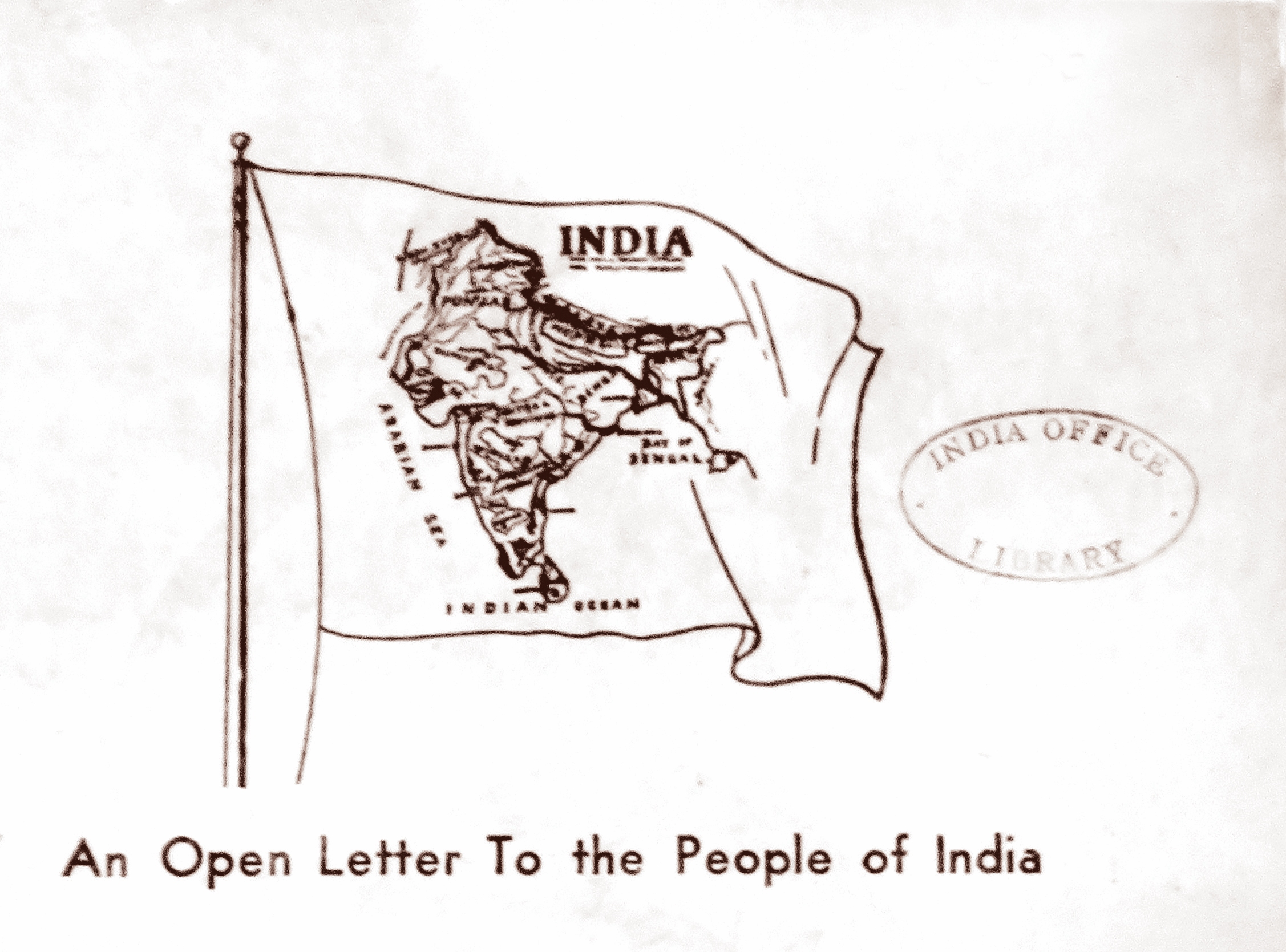

This two-page illustrated pamphlet was issued by the Hindustan Ghadr Party in the late 1930s, most likely on the eve of the Second World War in 1939.

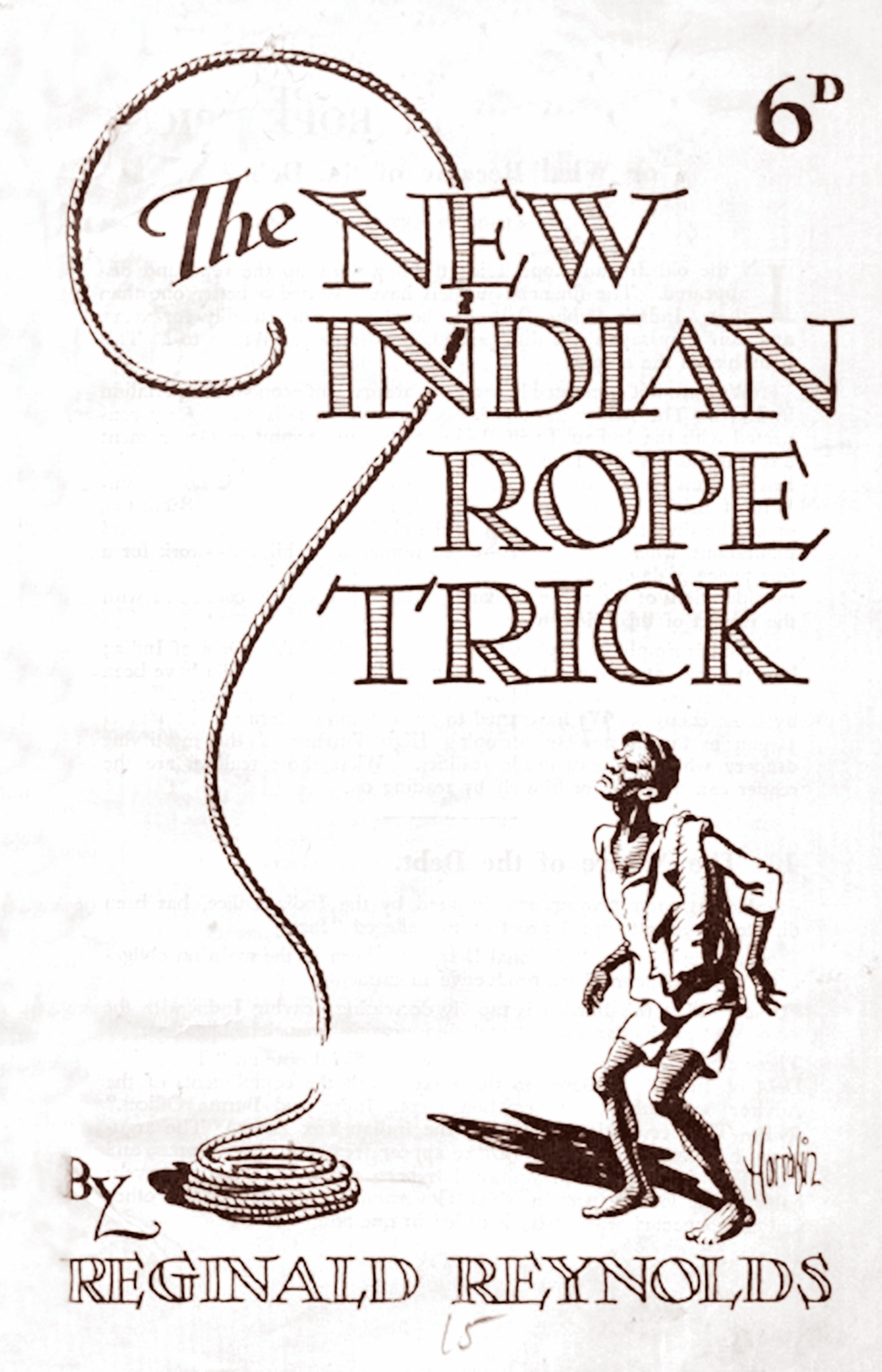

This sixteen-page pamphlet was published in the middle of the Second World War by the Indian Freedom Campaign Committee in London, and banned the next year, in 1944. Reginald Reynolds (1905–1958) was an investigative reporter and an associate of Gandhi who had been to India in 1929.

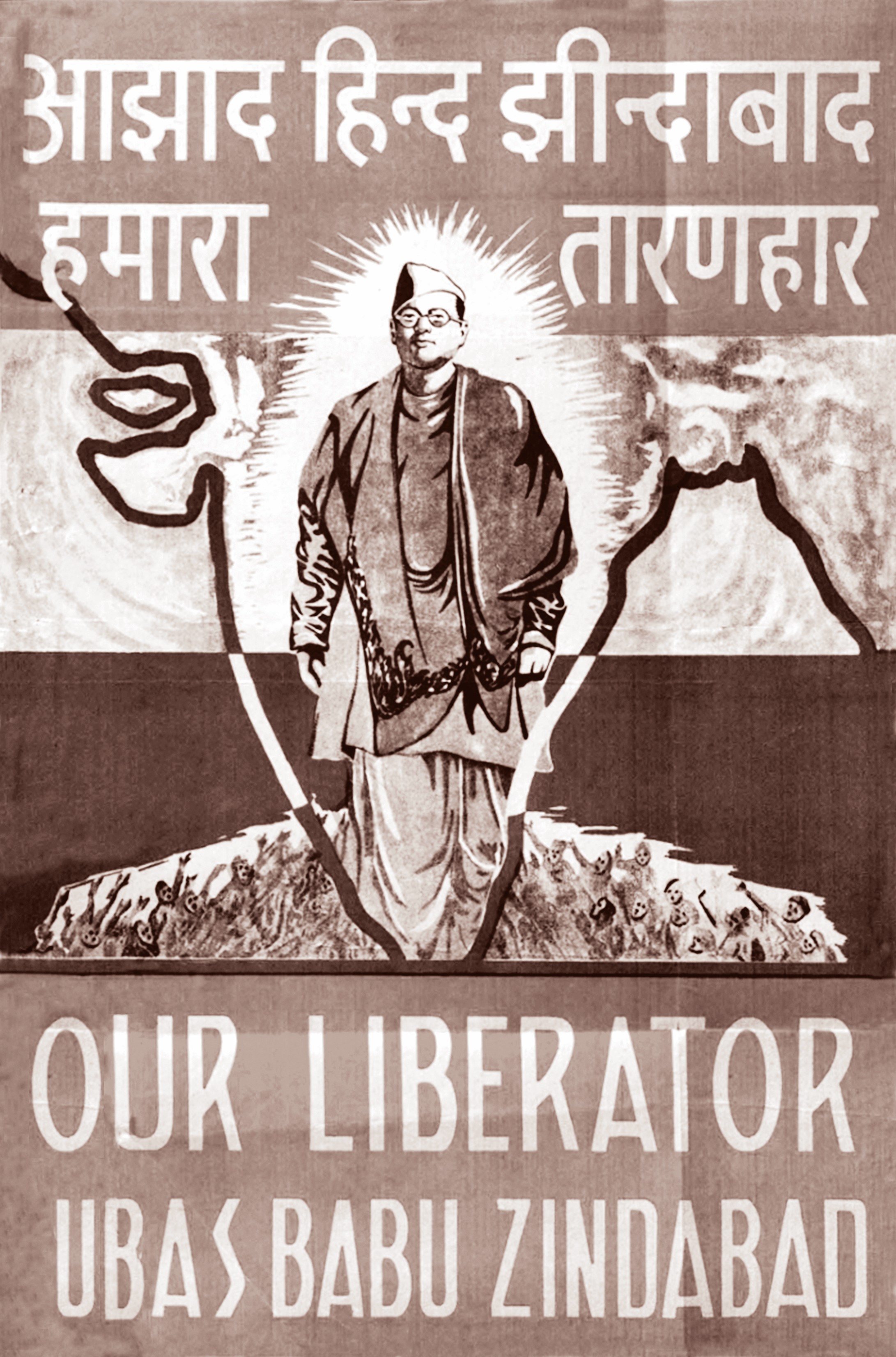

In 1942 the Government of India considered this poster to be a ‘prejudicial report’ (prejudicial to the ‘efficient prosecution of war’) under the Defence of India rules since it suggested that Subhas Bose had gone over to the enemy.

Conclusion

These lost gems from the Indian freedom movement include writings by figures famous and obscure, of events immortalized and forgotten, by Indians and non-Indians, by people jailed and free, by politicians and intellectuals, revolutionaries and students, and in several Indian languages. The well-known figures included in this selection include S.C. Bose, Bhikaiji Cama, Hay Dayal, M.L. Dhingra, M.K. Gandhi, Aurobindo Ghose, H.M. Hyndman, Shyamji Krishnavarma, M.M. Malaviya, S.P. Mookerjee, Jayaprakash Narayan, J. Nehru, M. Nehru, Lajpat Rai, C. Rajagopalachari, Sampurnanand, V.D. Savarkar and B.G. Tilak.

Each excerpt illuminates not just its author’s thought processes, but the times in which the text was composed and circulated. Some of these banned ideas are provocative even today while others seem tame; certain arguments have stood the test of time while others have lost currency.