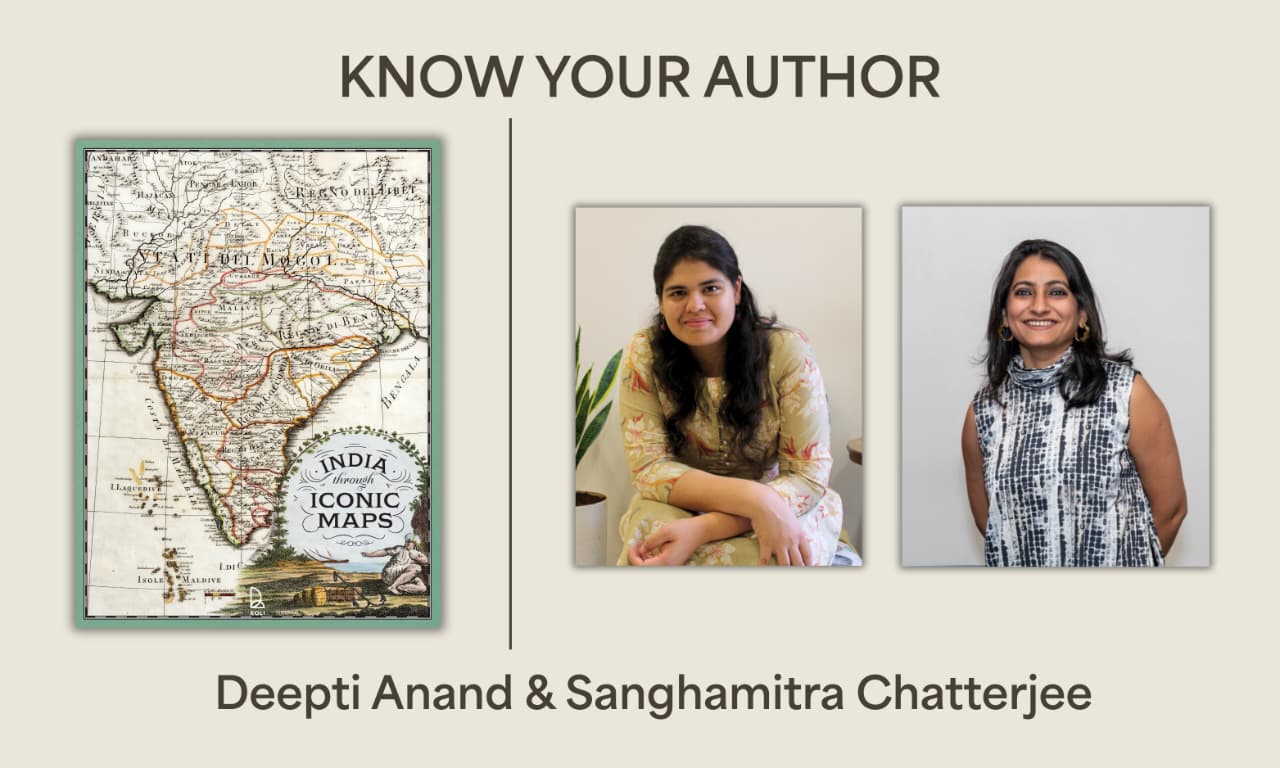

A treasury of cartographic splendour, India Through Iconic Maps presents over 250 exquisite maps – many never before published – spanning the subcontinent’s rich history from ancient cosmographies to the watershed 1947 Partition, where every map is a story of power, place, and imagination. With museum-quality reproductions and stunning design, this is a collector’s edition that celebrates the art and power of maps like never before. Here is a candid interview we conducted with Deepti Anand.

1. Which is your favorite map in the book and why?

It’s almost impossible to choose just one. Technically, I actually have different favourites – one just for its visual appeal, another for the story it tells, one for the drama around how it was made, and one for the thrill of decoding it. But if I really had to pick, it would be the Red Sea chart by a Kutchi sailor from the collection of the Royal Geographical Society. It’s just mesmerizing – the size, the colours, the notes everywhere, even the back covered in handwriting. Every time you look at it, you spot something new.

2. What is a fascinating fact you discovered while researching the book?

What struck me most was the evolution of mapping itself. Each map felt like a new adventure – I was constantly wondering what the next map-maker would uncover, how they would reach their conclusions, and what they would choose to emphasize. Within this, the most fascinating aspect was espionage. The stakes around geography were immense: sneaking copies of maps, borrowing knowledge, treating them as bibles of geography. Later, during the Great Trigonometrical Survey and the Great Game, disguise became a crucial tool for charting unmapped routes and territories across India and along its borders. These layers of secrecy, strategy, and subterfuge were endlessly fascinating to uncover.

3. What is your idea of happiness?

The feeling when you suddenly find that one piece you have been chasing in your research, often in the most random place. Or when a grapevine lead opens up a treasure trove, throwing up even more threads that complicate the research further – but in the most exciting way. That moment of discovery is pure bliss.

4. What was the most difficult part of researching/writing the book?

With research, the hardest part was knowing where and when to stop. Every map could have become a book in itself – every detail offered a new direction: the maker’s history, the patron, the iconography, the spellings, or a stray note scribbled in the margins. For the writing, the challenge was to stay within word limits while still saying enough to spark the reader’s imagination and curiosity. I also had to decide how far to carry the story – how to balance individual maps with the sense of evolution and continuity across time.

5. What is one piece of art, map, or textile you have come across in your years of research that you wish you owned?

I honestly wish I owned the original copy of the Catalan Atlas of 1375. It’s one of the most fascinating early attempts at capturing the world in a single compilation, full of wild guesses and gorgeous illustrations. You turn each leaf and you’re in a new part of the world, and you can lose yourself in it for hours. I remember the first time I came across the Catalan Atlas and noticed how India was shown on it. I must have spent hours just scrolling through, looking at every detail, and trying to figure out what was known of each region at the time.

6. When do you work best – day or night?

Night, without question. It is quiet – no calls, no meetings, no interruptions. This book was really born out of long nights that spilled into mornings.

7. If you were not an archivist, what would be your preferred profession?

Either a detective (the kind who relies on observation and deduction rather than forensics) or – this may sound completely different – but a DJ!

8. What is a favourite book of yours?

In fiction, The Palace of Illusions by Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni, and as an illustrated volume, The Curious Map Book by Ashley Baynton-Williams for an unusual but thoroughly engaging curation.

9. If you could travel to any era in India’s history to see how maps were made, which time period would you choose and why?

Honestly, I want to see them all! But if I had to choose: the sixteenth century, when map-making was this mix of research and guesswork – like puzzle pieces that never fit quite right. Also, I would have loved to be a fly on the wall at the Survey of India office during the Great Trigonometrical Survey in the 1800s. It must have been buzzing with energy and the hunger to map!

10. What role do you feel maps play in shaping national identity and/or collective memory?

An essential and almost foundational one – especially if we view them through a multidisciplinary lens. They hold far more than what we usually look for. They capture how people understood land: the lives lived within it, the politics of that moment, and the ways in which value was attached to the world around them. They are records of observation, interpretation, and memory and each map is a layered document of human experience.