Why We Eat

Our motivation to eat is self-evident; we eat to live.

More often than not, we observe that axiom overturned.

Humanity apparently, is living just to eat, shoveling in delectables as if there’s no tomorrow. Fact, not hyperbole. If we keep swallowing delectables at this rate, there will be no tomorrow – not for individuals, not for our species.

In a world where a child dies of hunger every ten seconds, where one billion people do not get one square meal a day, 1.9 billion suffer from illnesses induced by eating too many meals in a single bite.

That’s right: the foods that drive obesity contain enough energy to feed a family of four. These foods aren’t necessarily large in size, but they are concentrated in energy, most often from sugar and fat. Surely, we couldn’t be eating them just to stay alive?

We did, two million years ago. Back then, as we wandered long distances hunting and gathering, high-fat, high-sugar foods meant the difference between survival and death. The brain recognized them as superfoods. Unfortunately, the brain still does.

We no longer perceive these foods as lifesaving. Instead, we perceive them as delectable.

In most animals, eating is driven by hunger.

In us humans today, it is driven by taste.

Appetite is what we feel in anticipation of a delicious meal. If the meal is likely to be tasteless, we may eat out of a sense of duty, but there’s no joy in it.

We don’t eat for nourishment, we eat for taste.

It goes without saying that for food to nourish us, it must be tasty.

Unfortunately, most people regard ‘healthy’ as synonymous with ‘boring’. The word invariably produces a

grimace. ‘Tasty’, on the other hand, produces a twinkle in the eye.

Taste, as we experience it on the tongue, is perceived as sweet, salt, tart, bitter, and umami. This last, umami, is more sensing the molecule glutamate, rather than the food that contains it. There also is growing evidence of our ability to taste fat.

Most of the time, taste and aroma are perceived together. We have all experienced the loss of taste that accompanies a heavy cold. During the present pandemic, loss of smell and taste took on an ominous meaning, as they became the first informers of COVID-19 infection. (Anosmia and dysgeusia became common parlance. What cachet Latin gives to plain speech!)

In evolutionary terms, this twinning of the sensations of taste and odour informs the brain of what we can expect from this meal: nourishment or threat. Bitter and sour tastes, and ‘off’ odours are primitive signals of dangerous foods.

Today, the brief that the brain gives taste and odour is very different. The differentiation is between pleasure and, well, the not so pleasant. The brain registers pleasure by the release of chemicals that urge us to eat more. But the brain can’t take this decision without reviewing the state of affairs within the body. What is the energy level like? How empty is your stomach? Is it really time to eat?

The answer to these questions may be completely at variance with the urging of the pleasure signal.

And guess what, pleasure always wins.

You might will yourself to refuse that delicious gulab jamun or that crunchy chakli, but the desire is definitely strong. Whereas, if the brain operated on necessity alone, the very thought of that gulab jamun would make you sick.

So, we are stuck with a brain that shows a strong preference for the soft life.

No, it isn’t ‘weak character’ as some people persist in thinking. Far from it. The brain is a jury, and how it votes depends on the most persuasive opinion.

And the opinion, again, is swayed by need.

Haven’t you experienced the delight of a mouthful of rice, a sip of milk, or a morsel of banana when you’re hungry and tired after a long day’s toil? How tasty such plain fare seems then, and a prayer of gratitude escapes us without thought. At this moment, food has answered the need of hunger, and

the motive forces of hunger and pleasure are in complete synchrony. The same foods may not seem so tasty when you are more at leisure.

Taste is also heightened when we are hungry. That’s surprising. We need less sugar, less salt. We pass up that twist of lemon and can definitely do with less spice. Whereas, when we are not exactly hungry, it takes more of all these substances to convey taste. So, it is not a question of simply craving a taste – our ability to perceive taste is blunted when hunger signals are dampened. It is a persistence of evolutionary wisdom: nothing tastes good when your stomach is full, so why eat at all?

Why, indeed.

My experience with patients with Metabolic Syndrome leads me to believe that this dampened perception of taste is the most important reason for weight gain, obesity and insulin resistance – all leading up to diabetes.

The high-energy foods we eat with such eagerness reset our expectations of taste – so MORE! becomes the credo. More ‘taste’ becomes more high-energy, sweet, crisp, fatty foods.

Experimentally, it has been proved that insulin heightens the perception of taste. This is proved also in clinical practice every day. I wait for the moment when a patient reports that she ‘doesn’t enjoy spicy food anymore’. I know then that her insulin resistance is backing off, and I can expect her to improve quickly.

Let us sneak into the brain and see how it makes these decisions.

As food is tasted, information is whizzed off to lower brain centers, which then relay it to the cortex which will both interpret the taste and predict its value:

Will it satisfy hunger?

Will it give me pleasure?

When we are hungry, we continue to eat till we are satisfied. This produces the same response to two different ‘value’ foods: both pleasant and unpleasant. We continue to eat the pleasant food eagerly. But if only the other sort is available, we still eat till we are satisfied.

The pleasure factor overrides this. The brain dampens its ‘satiety’ signals for foods that are valued as pleasure-giving. So, we continue to eat them even when we are way past full.

It begins to look as though everything depends on the brain’s value system, so we must look at its work ethic.

This is the focus of intensive study, as can be imagined. How does the brain evaluate the worth of a food?

Studies show, rather shockingly, that the brain is a sucker for advertising. It rates foods that are attractively packaged and presented very highly, even when they are nutritionally empty. Similarly, labels contribute towards evaluating tastes and odours.

In one famous experiment, two groups of subjects were asked to smell the same odorant and required to state how appetizing it was. The odorants wore different labels. One read: Body Odour. The other: Cheddar Cheese.

You can imagine how that went down.

Labels that resonate with our value system influence our choice of foods. ‘Organic’, ‘Sustainable’, ‘Ethically Produced’ all press the right buttons no matter what the content. Expensive foods are rated higher. So are socially in foods.

The brain works just the way we consumers do: market happy, socially wired, and desperately keeping up with cool.

Does this mean that the evolutionary wiring of appetite and satiety that made us human is no longer sending out the right signals? Or does it mean that we aren’t giving it much choice?

Although when it comes to cuisine we are spoilt for choice, I still say the second reason applies.

To examine my conviction, over the next half hour, trawl the internet for the most popular recipes of 2021. You will come up with a variety of cuisines, sweet and savoury – but they will all have a common denominator of very high sugar and fat.

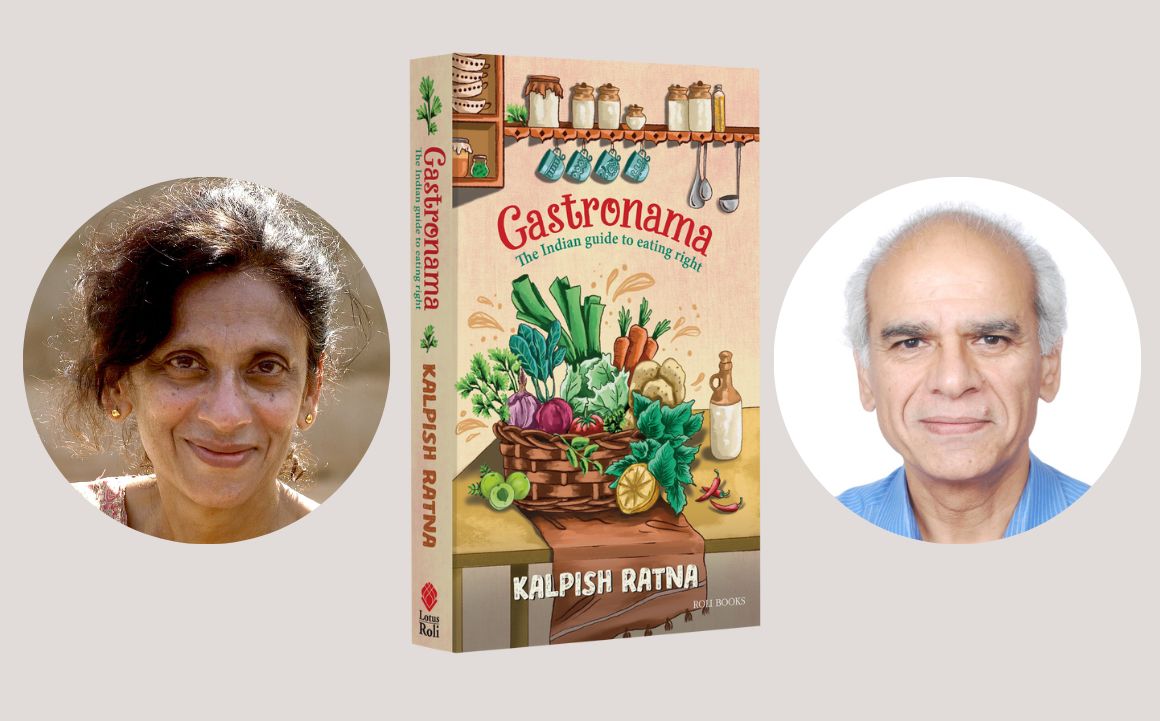

To continue reading, get your copies here.